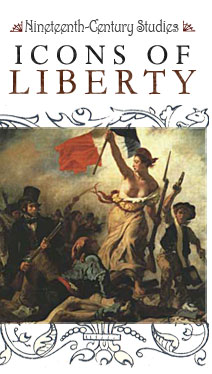

Introduction to Icons of Liberty

The roots of the iconography of Liberty can be found in the Roman Republic (510-44 B.C.), where Liberty was envisioned as a Goddess. She underwent a resurgence in the 16th and 17th centuries, when neoclassical artists bonded the iconography of Greek and Roman divinities with contemporary abstract ideas, such as Servitude and Concord. But it was not until the late 18th century that the neoclassical image of Liberty became ubiquitous and politically consequential. The neoclassical Liberty is always a female figure, usually partially nude, sometimes wearing the liberty cap (the Phrygian or slave cap of Rome that signified a slave had been freed), bearing the liberty pole, and crushing chains or the crowns of tyrants underfoot. Icons of Liberty were everywhere in the popular consciousness and public images of the Age of Revolutions, especially in France and in the United States. In the nineteenth century, representations of Liberty also flourished, but they multiplied, transformed, and evolved in curious ways. Just as the nineteenth century had to come to terms with the after-effects of revolutionary ardor, so too did nineteenth-century culture find diverging and multiform ways of representing Liberty in post-revolutionary contexts (the most important republican experiments of the nineteenth century happened in France, Great Britain, and the United States; this module's materials are therefore concentrated on these three nation's representations of Liberty).

Transformations of Liberty as an icon are complex in this period. We find a particular tension between pastoral and martial images of Liberty; the difference seems to follow from the artist or writer's sense of the degree to which the goals of Liberty have been achieved or the degree that Liberty is threatened by current political realities. Throughout the nineteenth century, the neoclassical image endured, but often merged with national symbols, such as the French Marianne, the British Britannia, or the Indian Princess or Columbia of the United States. This change reflects the widely-held beliefs of citizens of France, Great Britain, and the United States that each country uniquely expressed a commitment to political liberty in its national character. Dissenters and challengers to such self-affirming national propaganda also used the symbol of Liberty as a rebuke. The icon of Liberty was important to abolitionist rhetoric and visual culture, as it was to British Chartists and other opposition groups bent on political reform. In France, Liberty becomes a symbol of what the nation has lost through its post-revolutionary governance by emperors and monarchs, and when citizens took to the streets, as in the 1830 and 1848 Revolutions, Liberty was depicted as fighting side-by-side with the patriots at the barricades. Those who fought for national liberty for other European proto-nationalities (such as Poland, Italy, and Wales) also employed the figure of Liberty in their cause. Consequently, we find in various nineteenth-century political cartoons and illustrations that the French Empire, Austrian-Hungarian Empire, the British Empire, and the Franco-Prussian Empire all take their turns as the iconic tyrant who threatens Liberty or whose crowns or chains Liberty breaks. The nineteenth-century use of Liberty as an icon testifies to her flexibility-she was claimed by almost all parties and all nations, and transformed for a multiplicity of ends, even though she was honored in reality far less frequently.

Coins

Coins Commentary

Commentary Fiction

Fiction Historical documents

Historical documents Illustrations & Cartoons

Illustrations & Cartoons Paintings

Paintings Poetry

Poetry Sculpture

Sculpture Seals

Seals