Marvin Trachtenberg, The Statue of Liberty (1976)

Transcribed from pages 22-26, 66-68, 79-80, 100, and 186-188 of Marvin Trachtenberg's The Statue of Liberty. Published by The Viking Press, 1976.

1.

"To be properly understood, the origins of the Statue of Liberty must be seen in the context of French politics in the 1860s and early 1870s, French notions of liberty and republicanism (both associated with the image of the United States), and especially Laboulaye's political philosophy. For although the statue was destined to become a personification of the United States, it began as an expression of French ideas. The project for its erection in New York Harbor was, moreover, a French political ploy.

Laboulaye's career provides an easily identifiable thread running through the tangled skein of French politics in the last years of the Second Empire and the first of the Third Republic. An internationally distinguished jurist, he had been since 1849 Professor of Comparative Legislation at the Collège de France where his wit and imagination, no less than his strong republican convictions, made him a popular lecturer. His political outlook led him, early in his career, to the study of the great modern exemplar of republicanism, the United States. And after the death of de Tocqueville in 1859 he emerged as the leading French authority on American constitutional theory. A prolific writer, he published a three-volume Historie des Etats-Unis (1855-66), and a satirical story about a Parisian suddenly transported into an ongoing New York existence, Paris in America (1863), besides numerous tracts and articles which included a plea for the cause of the Union against the South, first published in the Journal des débats in 1862, translated into English and frequently reprinted in America. A scholarly nature, a retiring disposition and delicate health kept him from the center stage of French politics for most of his life. But he played a not inconsequential role in the last months of Napoleon III's reign when he somewhat surprisingly compromised his principles by giving support to the regime in the hope of liberalizing it. After 1870 he was, however, to salvage his reputation and to emerge within the charmed circle of republican leadership in the National Assembly. Although never a dominant public figue he contributed materially to his party's ultimate ascendancy.

The political situation in 1871 was characterized by Laboulaye as 'a moment when a bewildered France searches for its way but does not find it.' The instability of the French state since 1789 had acquired the appearance of a permanent condition. A succession of regimes, unwilling and unable to create true political equilibrium, had maintained only an appearance of stability and order by stifling opposition. But the ideas and energies released by the Revolution were not to be contained. Splinters of revolution continued to smolder beneath the surface after the restoration of the monarchy in 1815 and burst into flame at regular two-decade intervals—in 1830, 1848, and 1871. A monstrous political cycle seemed to have been established in a nation viciously divided against itself.

Under the Second Empire, even before the liberalization of press censorship in 1868, there were always indirect means for the opposition to express itself. A common literary device was to explore subjects distant in place or time in a manner calculated to make the reader reflect on contemporary conditions at home. The Emperor himself had resorted to such a mode of expression in his study of Caesar in the mid-1860s, asserting an autocratic ideology by reference to the Hegelian concept of the man of destiny—Caesar, Charlemagne or Napoleon I—who appears at a critical moment to save society and restore the authority of the state.

For the opposition America was a primary theme. Since its discovery, the New World had provided a region for the utopian dreams of many polemicists, the more notable including Voltaire and, in his more moderate way, de Tocqueville. Indeed, after 1776, America was often seen by the French as the realization of the political philosophy of the Enlightenment, the embodiment of Liberty and Reason. By the mid-1860s the United States—particularly after the victory of the Union—was the ascendant republic. And the French recalled that they had shared in its launching. Washington and Lafayette were still paired in patriotic speeches on both sides of the Atlantic. More specifically, the success of America appeared to the French as a synthesis of principles which seemed doomed for ever to incompatibility in their own country—order and liberty.

Laboulaye was a leading practitioner of the use of the American example to criticise home policy. Of his major works, mainly written under the censorship of the Second Empire, none was of purely scholarly motivation. All of them involved some degree of political intent and nearly all had the same theme, whether cast as a History of the United States—written with the avowed purpose of discovering the 'durable conditions of liberty' and presenting as a great revolutionary hero not Napoleon but Washington 'who reconciled the world with Liberty'—or as Paris in America, his still amusing satire of French attitudes to things American, especially liberty. Perhaps the most intense of his American writings—and the most relevant to our subject—was the widely circulated tract which he wrote in 1862 when the success of the Union was in doubt and the French were divided as to which (if either) side to aid. 'Frenchmen, who have not forgotten Lafayette nor the glorious memories we left behind in the new world—it is your cause which is on trial in the United States,' he wrote. 'This cause has been defended by energetic men for a year with equal courage and ability; our duty is to range ourselves round them, and to hold aloft with a firm hand that old French banner, on which is inscribed, Liberty'" (22-26).

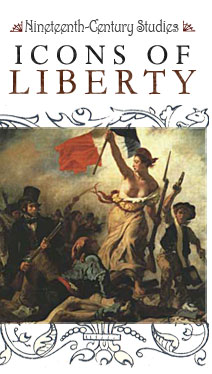

"The overt dynamism of the July Column Liberty was undoubtedly inspired by a better known work done just before it. In Delacroix's famous monument to the July Revolution—his Le 28 Juillet, La Liberté guidant le peuple aux barricades, painted in 1830 immediately following the uprising—liberty achieves a powerful impact mainly through a change in style. It is recognizably the traditional goddess that dominates the great masterpiece, complete with Phrygian bonnet. But, with a rush like the genius of the column, she now strides powerfully forward carrying aloft the tricolor and bearing a flintlock, rather than standing meekly with a scepter. At her feet are heaped the corpses of the battle for freedom in place of a neatly set cat and broken jug. She is not nude but her clinging drapery falls, baring her great breasts. Not a distant goddess of Olympus but of the earth and the people, she is the 'forte femme aux puissantes mamelles, á la voix rauque, auc durs appas' of Auguste Barbier's contemporary poem.

Although it was clearly the power of Delacroix's Neo-Baroque brush that triumphed, he too was not without help from traditional sources. The victorious spirit of his Liberty is not fortuitous: it has been shown that her rushing form was inspired by ancient personifications of Victory. Thus in both cases the process of 'pseudomorphosis' was crucial. In one instance an unimaginative academic sculptor simply borrowed a Renaissance Mercury intact, slightly recasting his role as messenger of the gods to one bearing a more contemporary message. In the other a great painter, whose genius lay so much in the power of authentic renewal of tradition, perceived in the dynamic movement of a Hellenistic type the means to re-animate a time-worn iconographic personage.

The ancient mold of Liberty had been shattered. When Bartholdi revived the theme a generation later there could be no going back to the pre-1830 form, particularly not in the case of a monument that was intended to carry a pointed message to a wide public. Yet the transformation of iconography in 1830 had not been without attendant problems. The barely visible Mercury-like figure atop the Bastille Column aroused little emotion. But Delacroix's work met quite another reaction. It suffered a long history that Bartholdi was certainly mostly aware of (if only through his teacher, the republican Ary Scheffer), and it served him as both inspiration and warning.

Delacroix's Liberty had been so potent an image for its time that, unlike the aloof genius atop the Bastille Column, it was treated by the government as dangerously subversive—banished to an obscure Louvre corridor after being reluctantly purchased from the Salon of 1831; then returned for better safekeeping to the artist himself in 1839; and disallowed even from temporary exhibition in volatile Lyon in 1848. It only returned to the public eye after the unpredictable Napoleon III, being assured of its quality as a painting, allowed its exhibition in the Salon of 1855. His instinct was right: by then it proved to be politically impotent, essentially because its romantic style already was quite old-fashioned, dulling its revolutionary edge (General Franco, it will be remembered, now seeks to obtain Picasso's once inflammatory Guernica for Spain). Purchased by the state, Delacroix's painting hung in the Musée du Luxembourg until the moderate republicans in late 1874, on the eve of their tentative victory, felt quite secure in placing the image in the Louvre as a symbol of their emergent regime (as well as being, perhaps, another testing of public reaction to their mode of artistic propaganda in addition to Bartholdi's Lafayette).

The ambiguity of Bartholdi's relationship to Delacroix's Liberty is evident. It was necessary to avoid truly revitalizing the powerful, revolutionary emotion the painting had originally provoked. Laboulaye, extremely cautious and sensitive to such questions—and who, let us remember, was an impressionable nineteen-year-old in 1830—in an important fund-raising speech of 1876 alluded deprecatingly to Delacroix's Liberty as 'the one wearing red bonnet on her head...who walks on corpses...' and felt that Bartholdi's more pacific image surpassed it. One can appreciate his sentiment. Laboulaye was a retiring man of non-violent principles, who shunned violent tactics in politics: Bartholdi had replaced Delacroix's rifle with an engraved tablet, and the aggressively waved tricolor with a torch of Enlightenment. Laboulaye was also a pious man, and a bachelor: Delacroix's Liberty was raucous, half-nude female, while Bartholdi's was decently covered up from the neck" (66-68).

"The ancient Goddess of Liberty had thus become not only a reincarnation of such old themes as Faith and Truth, but assumed in her own right a multiplicity of roles: martyr, secular saint, prophetess and romantic heroind—all achieved largely by reference, sometimes rather strained, to the traditional symbolic apparatus. This complex, multiple program of meaning served the purposes of the day, but was eventually to lose much of its integrity as the historical conditions of its creation faded. The unwieldy iconographic machinery rusted, leaving the observer with a kind of polymorphic iconographic blank that might be invested with a variety of changing, up-dated symbols. However, on one level, because of its ever increasing notoriety, the total configuration of the statue became itself the symbol of liberty: the image of a single work of sculpture took the place of the old idealist, allusive iconography Bartholdi had labored so hard to revive but which he succeeded only in embalming.

The fate of Bartholdi's program included as well the explicit theme of the project—the still unexplained fact that his Liberty was conceived, in a mode that we might call gerundive allegory, as 'enlightening the world.' ('Enlightening,' translated from 'éclairant,' carries here the archaic sense of 'illumination' as well as the more specific 'instruction' it has become. An up-dated translation of the original French title might well be Liberty Illuminating the World.) The phrase has become a disposable appendage (the figure now being simply termed 'the Statue of Liberty'), but for Bartholdi and his patrons it was essential. As in everything else about the statue the theme was not a particularly original one, neither as to its allegorical mode nor the topic of illuminant liberation. As one might have expected, the theme—ultimately stemming from St John's Neo-Platonic image of Christ as 'light of the world'—goes back to the revolutionary period, when it was widespread in political thought. Although the philosophy of the Age of Enlightenment stressed that true liberty only came to those graced by the power of reason, in more poetic iconography Liberty herself possessed powers of enlightenment" (79-80).

"Thus, Romantic Neo-Classicism, nationalistic aspirations and pride, and culturally pervasive materialism combined to make the nineteenth century a great period of the outsized monument and especially the colossus. As the mid-century became the late century the momentum of colossus building increased, topping out a thickening forest of monuments of more ordinary scale that almost threatened to choke the city squares and picturesque sites of Europe—so that at one point in Paris a moratorium on monuments was proposed. (Even in America, where ambitious statuary memorials were scarcer, there was the unrivalled 555-foot Washington Monument, 1848-84.) The Statue of Liberty marked the culmination of the movement.

"But soon all Liberty's creators were to pass from the scene, like ripples in water spreading from the center of a disturbance and subsiding. Several decades passed, and the old historical realities were displaced by new. Like an adopted child, the statue retained the hereditary physical form of its natural parents, but took its mature character from its foster home. The gesture and diffuse collection of attributes of the statue received much of their meaning from the historical context. When this was gone, the political allusion intended by Laboulaye and his colleagues was largely lost (not to mention the more shadowy, personal meaning it had for Bartholdi). For the Americans, there was no profit in maintaining the symbolism of international revolution (even on the intended moderate terms of the 'conservative republicans'). Few among the American public wished to be reminded of the frailty of the thirteen colonies in 1776, and how they had welcomed aid from a mighty nation that had since grown soft. And certainly whatever was sensed of the imperialist French undertones of the statue was felt as abhorrent. The purging of cumbersome allusion has been observed in the eventual shift of the statue's popular name: at the time of its appearance often called 'the Bartholdi statue,' Liberty Enlightening the World became simply The Statue of Liberty, the embodiment of the universal ideal in a particular work instead of the old incorporeal image. But this neutralization of meaning was equally valid for all the world. Had it been the only transformation of meaning Liberty would have been a statue without a country, as it were, and would have involved no special significance for the United States. What came to pass, however, was that Liberty acquired, simultaneously with her becoming a new universal icon, a close identification with her home, for she was not only neutralized, but naturalized as well. She gradually assumed something of deep American appeal.

As early as 1883 the French meanings were lost on Emma Lazarus. In her famous poem 'The New Colossus," the beacon of liberty seen across the sea was not intended to serve France or any other nation, but rather guide those Europeans eager for a new life away from Europe entirely, to the 'golden door' of America, where an uplifted torch was symbolic not of 'enlightenment' but simply of 'welcome.' Most Americans today are far removed from their immigrant ancestors' state of mind, so many of whom were, to one degree or another, Lazarus's 'wretched refuse,' particularly during the closing decades of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth. Moreover, most travelers now come to the country not by ship, but by airplane. The sentiment that the statue carried for millions of European immigrants who arrived before the 'golden door' all but closed in the 1920s has dwindled, although surviving as a pervasive folkloric theme. But in 1903, at the height of immigration, this sentiment was so widely accepted as expressing the statue's meaning that a plaque bearing the poem was affixed to the pedestal as an ex post facto inscription.

The experience of the immigrants involved crucial implications for Liberty. Their vision of America as political and economic liberation reinforced a natural tendency to perceive Liberty 'welcoming' as 'America welcoming.' The statue was becoming the image not so much of America the protagonist of Liberty, but simply America itself" (186-188).

Coins

Coins Commentary

Commentary Fiction

Fiction Historical documents

Historical documents Illustrations &

Cartoons

Illustrations &

Cartoons Paintings

Paintings Poetry

Poetry Sculpture

Sculpture Seals

Seals