Vivien Green Fryd, Art & Empire: the Politics of Ethnicity in the United States Capitol, 1815-1860from Chapter 8, "Liberty, Justice, and Slavery" (1992)

Transcribed from pages 185-200 of Vivien Green Fryd's Art & Empire: The Politics of Ethnicity in the United States Capitol, 1815-1860. Published by Yale University Press, 1992.

Liberty

Liberty as a subject in the Capitol belongs to the first phase of the building's artistic decoration, under Benjamin Latrobe, who determined to have a sitting figure of Liberty in the House of Representatives. The architect immediately contacted Philip Mazzei, who recommended Giuseppe Franzoni. (Giuseppe worked on the Capitol embellishment before his brother, Carlo.) Franzoni's Liberty held a liberty cap in her left hand and the scroll of the Constitution in her right, while her "foot treads upon a reversed crown as a footstool and upon other emblems of monarchy and bondage."

The plaster cast, which stood behind the speaker's chair in the Hall of Representatives and was destroyed in the fire of 1814, followed the iconographic tradition that had been established in this country after the Revolutionary War. Found in such precedents as Edward Savage's 1796 Liberty and Samuel Jennings's 1792 Liberty Displaying the Arts & Sciences, the ubiquitous pileus and pole are either held by the woman or located behind her, while the figures stand triumphantly over emblems of despotism. Savage's popular print, reproduced on embroidery, in amateur paintings, and on Chinese porcelain, features Liberty stepping on various regalia: a broken scepter, a hammer, and a medal. At the request of the directors of the Library Company of Philadelphia, who commissioned Liberty Displaying the Arts & Sciences, Jennings positioned a broken chain beneath Liberty's left foot, betokening the abolitionist sentiments of those Quakers who belonged to the society and had specified the work's symbolism. In both images, as in Franzoni's destroyed work, Liberty is conflated with Victory to demonstrate the triumph of freedom over tyranny and, in the case of Jennings's painting, over slavery.

Two points concerning the personification of Liberty and its association with southern slavery must be made. First, although objections to the cap would be raised during periods of sectional strife in the United States, it seems that no one opposed the presence of this object in Franzoni's Liberty. Second, the personification of liberty derives from ancient Rome, where the figure, Libertas, first stood for personal freedom in relation to manumission and later, in the Roman Empire, referred to both political liberty and constitutional government. It is the association between Libertas and manumission in ancient Rome that provoked opposition to the pileus during the 1840s and 1850s.

Benjamin Latrobe had not made this connection. Instead, the architect intended Liberty in the Capitol to denote only the meaning that had evolved in the Roman Empire, namely, constitutional freedom. In a long aside concerning "the welfare of our country," Latrobe wrote to Mazzei, "After the adoption of the federal constitution, the extension of the right of Suffrage in all the states to the majority of all the adult male citizens, planted a germ which has gradually evolved, and has spread actual and practical democracy and political equality over the whole union." Probably not intending to criticize his adopted country, the English-born Benjamin Latrobe's assessment in fact summarized America's limitations in defining its political equality and suffrage. At the outset of the nineteenth century, these ideals, as promoted by the founding fathers, applied not to all "adult male citizens" but just to Caucasian men. This distinction influenced later discussions over the meaning of the liberty cap and whether the symbol was appropriate given slavery in the United States....

What is important is how nineteenth-century Americans interpreted the work rather than the fact that they misunderstood its symbolism. Robert Mills's explanation of the sculpture's message shows that regardless of whether Americans were correct or incorrect in their identification of the allegory, they associated Liberty with the Constitution, indicating the direction later images in the Capitol would take. "'Be careful, my sons, to preserve inviolate the high trust committed to your charge,'" the Architect of Public Buildings envisions Liberty saying: "'be true to the principles of the glorious constitution established by your fathers, under my auspices.'" Going beyond an understanding of liberty as the umbrella under which the Constitution exists, Mills concludes this imaginary oration by having Liberty assert the Americans will "'be handed down to a grateful posterity as the firm upholders and preservers of the last hope of an oppressed world.'"....

Jefferson Davis's rejection of the pileus for Liberty in this cornice resulted in Crawford's transformation of the figural personification to History, a more innocuous allegory that avoided any associations with the "peculiar institution." As Captain Meigs explained to the artist, "Mr. Davis says that he does not like the cap of Liberty introduced into the composition. That American Liberty is original & not the liberty of the freed slave—that the cap so universally adopted & especially in France during its spasmodic struggles for freedom is desired from the Roman custom of liberating slaves thence called freedmen & allowed to wear this cap."

In Meigs's account, the slaveowner and future president of the Confederacy expressed knowledge of the practice of manumission in ancient Rome. During the Roman ceremony, freed slaves covered their newly shorn heads with the cap while magistrates touched them with a rod (the vindicta). Before the Roman Empire the cap symbolized emancipation from personal servitude rather than constitutional political liberty. Edward Everett also understood the meaning of the pileus, which he explained in a letter to Hiram Powers as the reason why Powers's intention to have his statue America hold the cap aloft constituted an inconsitency. This statesman had encouraged Horatio Greenough to base the composition for his statue of George Washington on the Pheidian Zeus and had earlier served as the chairman of the Department of Greek Literature at Harvard. Everett thus had studied antiquity and knew well the original meaning of the liberty cap. In his reconstruction of the pileus's origin, Everett explained that emancipated slaves in Rome wore a cap in order to hide their shaved heads, "hence 'to call a slave to the cap' was tantamount to liberating him or declaring him free."

Although both Edward Everett and Jefferson Davis provided accurate explanations for the original function and meaning of the liberty cap in ancient Rome, eighteenth-century emblem books had codified Libertas as a female personification who holds a pole surmounted by the pileus. Paul Revere employed the figure with a cap on the pike, possibly for the first time in the American colonies, in 1766 on the obelisk for the celebration of the repeal of the Stamp Act. Twenty-four years later, Samuel Jennings used Libertas in Liberty Displaying the Arts & Sciences not as a symbol of political freedom but as a reference to the possible emancipation of blacks in the United States, an appropriate meaning given that Jennings executed this painting for the Library Company of Philadelphia in support of the directors' abolitionist activities. In the work, Jennings juxtaposes a benign and beautiful white woman as Liberty with the slaves in the lower right-hand corner. In the background, a group of African Americans dance around the liberty pole in celebration of freedom.

This first abolitionist painting emphasizes the meaning of the liberty cap in the United States. Because it had referred to manumission in ancient Rome, the pileus in the United States resonated with tacit implications in regard to the slaveholding South. Consequently, the liberty cap and staff that Augustin Dupré depicted on the coin Libertas Americana in 1781 disappeared from the first American pattern dime of 1792. For the newly established country, which depended upon the link between the North and South for its existence, some Americans considered the symbols of Roman manumission too loaded in content for their inclusion on American coins....

We can now understand why Jefferson Davis opposed the use of the liberty cap in Crawford's cornice figures. Davis used his position as the person in charge of the Capitol extension between 1853 and 1857 to reject any potential anti-slavery implications. At the same time, Montgomery Meigs, although a northerner who considered slavery an "eternal blot" on the concept of liberty in the United States, communicated Davis's opinions and acted as an intercessor on behalf of southern concerns by making sure that the liberty cap and slavery remained out of sight in the Capitol artworks. This army officer had befriended a number of powerful southern politicians, among them Robert Toombs of Georgia and R.M.T. Hunter of Virginia, and he needed the support, as well as that of his boss, during the times when Thomas U. Walter and, later, Secretary of War Floyd challenged his position as supervisor of the Capitol ectension.

Jefferson Davis's rejection of the liberty cap as an anti-slavery symbol and Montgomery Meigs's adherence to his superior's desires are apparent not only in Crawford's doorway figures but also in his more conspicuous Statue of Freedom, which overlooks the mall. The idea for a statue on the pinnacle of the newly designed dome first arose in a drawing by Thomas U. Walter. The Philadelphia architect had conceived of a colossal statue of Liberty with the pileus on the end of a pike held by the woman. Upon learning about the plans for sculpture on the new dome, Meigs first asked Randolph Rogers for proposals. Rogers, occupied with his bronze doors for the Capital Rotunda, pleaded that he did not have time for additional work. Meigs next contacted Thomas Crawford in May 1855. "We have too many Washingtons, we have America in the pediment," Meigs reasoned in a letter to Crawford, noting also that "Victories and Liberties are rather pagan emblems." Nevertheless, the engineer concluded, "Liberty I fear is the best we can get. A statue of some kind it must be."

Crawford followed the engineer's advice and proposed "Freedom triumphant in Peace and War." In this first design, Freedom does not have the pole, cap, or any other symbols associated with Liberty. Instead the modest, softly rounded female figure wears on her head a wreath composed of wheat sprigs and laurel. "In her left hand," Crawford elaborated, "she holds the olive branch, while her right hand rests on the sword which sustains the shield of the United States." The sculptor also placed wreaths on the base, "idicative of the rewards Freedom is ready to bestow upon the distinction in the arts and sciences." Crawford thus merged Peace (identified by the olive branch) with Victory (identified by the laurel leaves) and Liberty in his drawing, creating an iconographic synthomorphosis (fusion of stock allegorical imagery) that would undergo additional metamorphoses based on Jefferson Davis's suggestions.

Four months later, Crawford submitted an altered design in which he abandoned the theme of peace and established more clearly the work's reference to Libertas. In the final model, which included some further, crucial modifications, the sculptor positioned what he now identified as "armed Liberty" on a globe is surrounded by wreaths placed below "emblems of Justice." Crawford added three emblems: "a circlet of stars around the Cap of Liberty"; the shield of the United States, "the triumph of which is made apparent by the wreath held in the same hand which grasps the shield"; and a sword held in her right hand, "ready for use whenever required." Crawford finished the statue by placing stars upon her brow "to indicate her Heavenly origin" and by locating the figure above a globe to represent "her protection of the America[n] world."

In Crawford's design, the artist added the liberty cap, elminated the olive branch and its reference to peace, and retained the sword. The addition of the globe as the "American world" corresponded to the vision of America as a great empire that would influence other nations to adopt its republican form of government. The orb also suggests an association with the nation's expanded view of manifest destiny as encompassing Cuba and the Caribbean. Like his Justice and History above the Senate door, Crawford's "armed Liberty" thus reflects the militaristic rhetoric of the 1850s and matches the administrative responsibilities of Jefferson Davis as the secretary of war who advocated the purchase of Cuba and Nicaragua.

Jefferson Davis once again objected to the pileus, arguing that "its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved"—quite an assertion from a slaveowner who argued vehemently on behalf of the slave system and its extension into newly acquired lands. This southerner's refusal to acknowledge that blacks in the South and on his own plantation were not born free indicates a dangerous racism implicit in the reasoning of the future president of the Confederacy. Davis suggested that "armed Liberty wear a helmet" instead of the liberty cap since "her conflict [is] over, her cause triumphant." Consequently, Thomas Crawford dispensed with the objectionable object, putting in its place "a Helmet the crest [of] which is composed of an Eagle's head and a bold arrangement of feathers suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes." Crawford furthermore placed the intials "U.S.A." on armed Liberty's chest, with rays of light issuing forth from the letters.

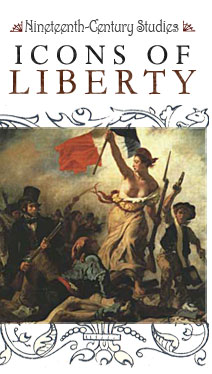

This third and final version of the dome statue of Liberty addresses concerns about Indians and slavery. Freedom, according to the artist, remains the focus of the statue, whether in the official title, Statue of Freedom, preferred by the current (1991) Architect of the Capitol, or the more accurate title given by Crawford and used by Jefferson Davis, Armed Liberty, which accurately conflates the two ideas manifest in this combined rendering of Minerva and Liberty. As Marvin Trachtenberg has demonstrated, after 1830 in France the personification of liberty had undegone a process of synthomorphosis in which artists fused iconographic traditions, as in Augustin-Alexandre Dumont's Genius of Liberty (c.1840), where Giovanni Bolonga's Mercury holds a flaming torch and a broken chain. Eugène Delacroix's 1830 Liberty Leading the People, executed to commemorate the July 30 uprising in Paris, also exemplifies the iconographic transition of Libertas. Instead of representing a classical goddess, Delacroix rendered a French revolutionary woman who holds the tricolor flag and rifle while wearing on her head the Phrygian bonnet. As Trachtenberg observes, "At her feet are heaped the corpses of the battle for freedom in place of a neatly set cap and broken jug." These two French works provide the basis for Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi's famous Liberty Enlightening the World (1886), better known as the Statue of Liberty. The French sculptor applied a syncretistic approach, uniting Faith, Truth, Eternal Felicity, and Divinity, among other traditional allegories, to provide the ancient goddess of libertas with a range of associations that evoke its intended meaning: the enlightenment of the world.

Executed twenty years after Crawford's Statue of Freedom was first set atop the Capitol dome, Bartholdi's statue provides a basis for recognizing the process of synthomorphosis. As in the New York harbor statue, Crawford's work discards the traditional symbols associated with Liberty, making the title (Statue of Freedom or Armed Liberty) crucial for our identifying the personification. Albert Boime has argued that Bartholdi's monument dispenses with the Phrygian bonnet to emphasize "the calming power of reason rather than...a fervent call to unceasing battle." Given that this American icon was created by a Frenchman and sponsored by those in France who had opposed the Commune, the omission of the cap has more to do with the bloody civil war in Paris than with concern in the United States over slavery in the South and its threat to national cohesion. Crawford had earlier chosen a placid image in his Armed Liberty, in part to show that Liberty's battles had been won in North America, enabling her to stand watch over the Union and the world to enforce her rule by the sword wherever and whenever necessary.

Jefferson Davis's rejection of the liberty cap and his recommendation of a "helmet" led to Crawford's conflation of three traditional allegories: Liberty, Minerva, and America. (Minerva will take on special implications because of the statue's location over the globe of the world.) As a result, Crawford created an image that loses its power rather than retaining its sharp iconographic focus. An examination of how Crawford's Statue of Freedom fuses three traditional allegories in a synthomorphic process will expose the monument as a study in compromise and the erosion of a sculptural goal.

America, as a female personification of a geographic location, came to symbolize the New World in the form of an Indian queen. Wearing a feathered skirt and a headdress, this America often held a club or a bow and arrow. The United States adopted this iconographic type as its own on three Congressional medals commissioned between 1787 and 1791 and on Augustin Dupré's diplomatic medal of 1792. Before and during the Revolutionary War, America and Liberty combined to become America as Liberty, in which the Indian princess with tobacco leaf skirt and headdress held the cap and pole, as in Paul Revere's masthead for the Massachussetts Spy. (Randolph Rogers followed this tradition in his personification of America in the Rotunda bronze doors, as did Constantino Brumidi in his frescoes.)

That Crawford added eagle feathers to the helmet indicates that the sculptor knew the tradition of associating America with Liberty and intended to combine the two allegories in his statue. In doing so, he created a figure that is often misidentified as an Indian, an ironic mistake given the stereotypical aboriginal images that decorate the Capitol and their evocation of the Vanishing American myth that advocated the Indian's destruction. Indeed, aside from the headdress, nothing on the statue, least of all its physiognomy and clothing, resembles the other Indian images at the Capitol nor in the history of American art. The figure is neither ignoble nor the noble savage, but instead a substantial woman swathed in classically inspired clothing who stands proudly and triumphantly over the globe of the world. If the statue indeed represented an Indian, the work would indicate the original inhabitants' triumph over white Americans and their rule of the continent, suggesting a different mythicohistorical ideology from that which pervaded and still pervades the American consciousness and the iconographic program of the Capitol.

Crawford's synthomorphic approach is further evident in the work's association with Minerva, the ancient Roman goddess of war and of the city, protector of civilized life, and embodiment of wisdom and reason. A majestic and robust female figure, Statue of Freedom in fact emulates Phidias's fabled Athena Parthenos, a work reconstructed by Quatrèmere de Quincy (and entitled Minerve du Parthénon) in Restitution de la Minerve en or et ivoire, de Phidias, au Parthénon (1825), which Crawford must have consulted. Phidias's Athena Parthenos was the guardian deity over that earliest and most archetypal democracy, Athens, and hence an appropriate prototype for the American female colossus who stands guard over the United States. Although Crawford's image is less complex, both the ancient and the modern works include the helmet, the breast medallion, and the shield along the side. (Crawford replaced the image of Medusa found in Minerva's breastplate with the initials "U.S.A.") Even the fluted cloak that gathers from the lower right to the upper left shoulder corresponds in these two matron types, whose immobility, severity of facial expression, military accoutrements, and colossal size express sternness and control, very different from the serenity and suppleness of Crawford's first design, Freedom Triumphant in War and Peace. (Crawford's final militant, motionless, and massive female resembles Luigi Persico's War, located in the left niche of the central doorway of the Capitol portico.)....

Although Thomas Crawford managed to complete the model for Statue of Freedom before his death in 1857, the workers did not erect the statue until 1863, the year of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Battle of Gettysburg. The outbreak of the Civil War resulted in the cessation of work on the Capitol extension and the temporary interruption of the statue's molding into bronze under the direction of Clark Millby. President Lincoln ordered the work resumed, however, despite some arguments that troops needed the bronze for munitions. "If people see the Capitol going on," Lincoln argued, "it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on."

Thomas U. Walter and the secretary of the interior, John Palmer Usher, orchestrated a ceremonial installation of the statue on December 2, 1863. Instead of having prominent statesmen and orators deliver speeches, the organizers arranged for a battery of artillery to be placed on the grounds east of the Capitol; it fired a salute of thirty-five rounds, one for each state, while an American flag, hoisted at the outset of the celebration, waved above the work. The government thereby coordinated a ceremonial military ritual to symbolize the nation's reunification under northern hegemony. As a writer in the New York Tribune asserted, Statue of Freedom stood triumphantly over the Capitol "now that victory crowns our advances, and the conspirators are being hedged in and vanquished everywhere, and the bonds are being freed." Freedom now turned, according to the article, "rebukingly toward Virginia," with an outstretched hand to guarantee "national Unity and Personal Freedom."

Thus by the time Crawford's Statue of Freedom surmounted the Capitol dome, the fasces—which Crawford identified as "the emblems of Justice triumphant"—and the wreaths that uphold the circular globe assumed new connotations. In the 1850s, when Crawford completed the plaster cast, armed Liberty's position above the "American world" alluded to the nation's vision of its great republic as empire in the western hemisphere. By the time of the Civil War, however, the statue's external symbols deflected attention from internal sectional differences and predicted the triumph of the North over the Confederacy. Justice triumphed in the New World with the freeing of the slaves and the Northern victory, enabling armed Liberty to stand even more proudly over the globe in anticipation of enforcing republican democracy throughout the world.

The elmination of the traditional liberty cap from Crawford's monument did not go unnoticed by some northerners, who commented on the implicit racism involved in Jefferson Davis's rejection of "the grand old Cap of Liberty," as an 1863 article in the New York Times fondly called the emblem that "our grandfathers [loved]." The anonymous author attributed Davis's decision to replace the cap with "the barbarous device" of the helmet to his "worshipping slavery." By this time, Davis had become the president of the Confederacy and was thus identified as the arch-defender of slavery.

Other northerners viewed the statue's symbolic content as significant. The New York Tribune reported on December 10, 1863, that the superintendent had gone on strike in Mills's foundry, in Blandensburg, Virginia, demanding an increase in wages. In the midst of this crisis, one black man offered to take the striker's place. "The black master-builder lifted the ponderous uncouth masses and bolted them together...til they blended into the majestic 'Freedom,' who to-day lifts her head in the blue clouds above Washington, invoking a benediction on the imperiled Republic!" The article concluded with the question, "Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist, and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?" If Jefferson Davis knew that a soon-to-be-emancipated slave had molded Crawford's statue, he did not acknowledge the irony.

Coins

Coins Commentary

Commentary Fiction

Fiction Historical documents

Historical documents Illustrations &

Cartoons

Illustrations &

Cartoons Paintings

Paintings Poetry

Poetry Sculpture

Sculpture Seals

Seals